NAGC 2012

As George Betts pointed out today or last night on FaceBook, this year’s convention of the National Association for Gifted Children was perhaps the most polarized, fiercely divided convention in recent years. A year ago the organization’s president, Paula Olszewski-Kubilius gave an address that argued the need for the field to come together under the umbrella of a new and singular definition of giftedness, of a unified concept that could and should direct both educational programming and research—Talent Development. It is unlikely that she had any idea before she gave that speech advocating unity that it would unleash a firestorm of controversy and develop over the following months a split just about as intense and fraught as the current split between America’s political parties.

Oddly, my own experience of the convention was extremely positive overall. Others who share my focus on the internal world of the gifted child, and on the fundamental developmental differences between the gifted and other children, had been stirred up by such an overt challenge to and dismissal of their perspective. They showed up to any sessions that fit that perspective with an unusual level of passion. I doubt that in the more than 25 years I’ve been attending and speaking at NAGC I’ve ever experienced more enthusiastic and responsive audiences.

As usual, the Columbus Group gathered after the convention, to share with each other our experiences over the last year and consider what we as individuals and—now that we’re out in the open—as a group, can and should do going forward. I arrived home wiped out and faced with only two days to get ready for Thanksgiving. I’ve been home now for a week, and my mind has been seldom at rest as I’ve pondered my experiences in Denver.

Patricia Gatto-Walden and I did a presentation this year, titled “What the Kids Want You to Know: It’s My Life.” A group in the UK 20 years ago took the keynote of the World Conference (a speech focused on gifted education as a way to make the best use of each culture’s natural resource of bright kids to benefit their country) to the kids at summer camps for the gifted and asked for their feedback. Taking a cue from them, we read aloud the shortened version of Paula’s speech that appeared in Compass Points to our Yunasa campers. Expecting no more than a handful to show up, we invited anyone who wanted to respond to it to share their thoughts for an hour long session. So many kids (nearly a third of the campers) were willing to give up regular camp activities for that hour, that we could barely fit them into the room we had available. They spoke enthusiastically for the full hour and several of them asked afterward that we send them the full text of the Subotnik, Worrell and Olszewski-Kubilius monograph that had formed the foundation for Paula’s speech.

Few of these kids knew anything about NAGC, and one of the first questions they had was, “Does this organization have kid members?”

We said it does not. Quite naturally, the kids thought this was outrageous—“How can it be for gifted kids, then? Don’t they get it that we have pretty good ideas about what we need? Do they think we don’t think about education during all the time we’re in school?”

What shocked me was not their question, but that I had never asked it myself. I’ve been aware, of course, that schools bring kids to NAGC, most often to perform, sometimes to serve as panel members in a session or two. But kid members? I hadn’t considered it necessary.

A Moment in the Wayback Machine

From the time my five year old son had the “head-on collision” with school that led me to begin learning everything I could learn about gifted kids, I have thought that it isn’t really the existence of kids with unusual intelligence that creates a need for specialized “gifted education,” it’s the way education is structured in this country and in most of the rest of the world. It’s a factory model created well over a hundred years ago and it has changed only slightly since. Children are treated pretty much as interchangeable cogs (or, with an emphasis on product, as “widgets.”)

At the very first gifted conference I ever attended a speaker said, “If God had known what schools would be like, He wouldn’t have made kids the way he did.” I thought it was a clever statement, but its full impact escaped me at the time. After all, school was school! I’d known what that meant since my October birthday allowed me to start kindergarten at age four in a system with a December cut-off date.

In the 1980’s, when I had begun to write and speak about the needs of gifted kids, I said in several talks that if school were done differently, we wouldn’t need the designation “gifted kids.”

People invariably argued with me, pointing out that gifted kids would still learn faster, more broadly, more deeply, and more connectedly than others and we’d still have to diagnose those learning differences. I agreed that gifted kids wouldn’t vanish—but that if we found a way to individualize education to meet the needs of every student, doing the same for the gifted would be just part of the deal. I kept remembering what my son said one year when I asked him after we’d moved—yet again!—whether the kids at his new Quaker school would tease him for wearing Kmart sneakers instead of the currently popular expensive brand. “Mom! Nobody teases anybody for being different in a school where everybody’s different!”

The absolute joy of that school was that the children were treated as individuals. Yes, they went to classes mostly based on age, but within those classes, probably because of their specifically Quaker focus on that of God in every person, each child was respected for being him or herself. But it was a small school and “everybody knew” (including me) that the whole country’s public system just couldn’t afford to be run that way.

When that school ran out of grade levels for my accelerated son, I briefly considered homeschooling, because we lived in Norfolk, VA, the only city in the USA where at that time homeschooling was legal. I’d been reading John Holt’s Growing Without Schooling and conversing with him by mail for a couple of years by then, loving his ideas and the freedom they provided for the kids. He didn’t focus on gifted kids–just kids. A friend of mine had illegally homeschooled her son back in Ohio (which had necessitated “hiding” him in the house all day every day) and insisted that it was the only way to individualize sufficiently to truly meet the needs of an exceptionally gifted child. But it was not in the cards for my family—I didn’t have the necessary patience and my extraverted son was horrified at the whole idea and refused even to consider it.

What Do We Mean by Child?

As I’ve thought about how the two sides in the current definition argument might possibly come together, it has occurred to me that maybe gifted isn’t the problem word. The problem word is child. Why does NAGC not have child members, when its stated mission is to serve children? Because today children are still defined by the field of education not as young individual human beings with individual needs and minds and drives and lives, but as a class of beings in need of being taught by adults what they presumably will need to know when they become adults.

There is an extent to which that definition makes sense, of course. Children have a lot to learn and there’s a long period of dependency during which they need to be sheltered, touched and held and cared for, fed and dressed. Human children need to interact with other humans (though not exclusively with adults) to learn language. Much of what they learn begins with observation and imitation. And of course there are all those tricky things like silverware to handle, stairs to navigate, windows not to fall out of, streets to cross. Plus there are reading, writing and arithmetic, which many of them will first be exposed to in school.

But what we believe about children has changed. There was a time when a child was thought to be an empty vessel, waiting for adults to fill it up with information. (Just last year I saw a YouTube about educational reform that actually still said this!) Science long ago showed that belief to be in error. Human children are learning creatures determined to explore and manipulate their environment, to test and try, to build and tear down, to question and experiment and interact with whatever other living creatures they encounter—all of which can be classed as “play” in the early years. And today in any household with technology, they mostly find a way either to use that technology on their own or get someone to show them how.

The sooner we put them in “school” where the primary activities are to sit still, be quiet, listen, wait for and then follow directions, answer questions “correctly,” and judge themselves in terms of how other children are doing at these tasks, the sooner we begin to limit their natural modes of learning. Instead of play that expands their experience and mastery, learning becomes what they do (or rather what they are directed to do) in school. There is very little difference in what they are directed to do, one student to another, and little if any concern about individual interests or personal choice. Natural learning gives way to coercion, solitary activity directed toward a predetermined goal, and a teacher’s external validation or criticism of their efforts.

(One could ask oneself just what sort of adult life these “lessons” are designed to prepare them for. Factories, yes. But factories are either in other countries now or use a lot of robots. Schools should not be in the business of programming human robots!)

Meantime, as the Yunasa campers told us last summer, the adults don’t ask them what they need or listen to them when they express their needs anyway.

And What Do We Mean by School?

Like it or not, times have changed! How often have you heard one adult say to another, who is struggling with some aspect of current technology, “what you need is a ten year old.” When my now nine year old grandson was two, he was already more adept at using his father’s computer to find what he wanted to interact with on the internet than I was. Now he scoffs at my efforts to learn something new on my “too smart” phone. It isn’t only theory that tells us that learners can be teachers and teachers learners. It is our everyday lives. And there is a tsunami of information available to and through the new technologies that kids are more adept at finding than many of us.

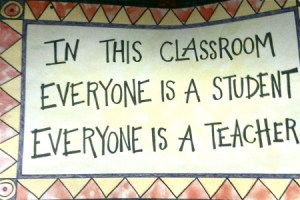

It is long past time to give up schools or redefine them as learning communities, where it is not just age that creates groups, but interests (passions), knowledge, experience and needs. In such learning communities there could be webs rather than boxes–language, math, history, geography, art, meant to be dealt with separately in small blocks of time–webs that could interweave what is known in service of creating something new, or helping the learner to grasp new information and move into and understand greater complexity. And children need to have a voice in how such learning communities would or could operate; because children are unhampered by the structures and restrictions of prior experience; they lack our long memory of “how it has always been” that would hold them back from imagining how it could be.

Our gifted kids, so very interested in learning, so passionate about exploration, could genuinely help to lead the way. One of their major differences (at least until we squash it out of them with work sheets and grades and gold stars and tests, grade point averages, boundaries and limitations) is their rage to learn and understand, and to do something with meaning. Those same kids who discovered at two how to find what they wanted on a computer screen, have ideas about how learning can happen, progress and change. And how the technology so many of them love and the games so many of them play, could enhance learning for themselves and other kids. They could work with adults who are willing to collaborate on finding the best ways forward rather than determining and dictating those ways!

Teachers who love their profession and have passion for their subject matter could, in learning communities, be freed to practice that profession instead of struggling to prepare a broad spectrum of kids in a narrow age range to succeed on standardized tests that really can’t measure either student learning or teacher competence.

We can’t have what we can’t first envision. And we are in a deep and dreadful rut. I started a Face Book page (www.facebook.com/deependxgifted) last November in hopes that those who visited it could begin thinking in new ways and sharing their visions about how education could happen if we began over again without schools. We didn’t get far. FB pages aren’t that great for collaborative thinking—everything gets pushed down the page and disappears. But that doesn’t mean the discussion shouldn’t be taking place.

We have to find a way to make things work better. I would welcome the best ideas of the Talent Development folk, but I would want them to acknowledge the existence of kids whose inner experience of the world really is different from the beginning. It isn’t just our field that’s in crisis and conflict. Our whole world is at stake. Pretty much really! New thinking, new ideas and new partnerships are essential as everything continues to change at warp speed. Let us outsource factory schools to some other planet so that we don’t have to find ways to keep squeezing human children into boxes designed for widgets or robots.

I end all my talks with the following quotation, meant for every human, child or adult, because we need to know that we are not interchangeable!

“You are not accidental. Existence needs you. Without you something would be missing from existence, and no one could replace it.” –Osho