A while back I titled a blog post Deep and Deeper and my last post, Who Are We?, led me to return to the intention that motivated that earlier post. Death (along with individual identity) is certainly a subject that can be described as deep or yet deeper. So deep is the subject of death, in fact, that many, perhaps most people in our culture, do their best to avoid talking or even thinking about it altogether.

Back in 1992, when the five women who began the Columbus Group, gathered at my house in Columbus, Ohio to try to come up with a different definition of giftedness than was currently in vogue (a definition centered on academic achievement) one of the very first examples of the qualitative difference between highly or profoundly gifted children and other children of their age [the difference we would soon name Asynchronous Development], was the case of Jennie–and death. Four year old Jennie was traumatized when her grandfather died. Extrapolating a principle from one subject or event to another, as profoundly gifted children tend to begin doing even as toddlers, she began to worry that her mother or father might die as well. Her mother, doing her best to comfort this very little girl, told her that she didn’t need to worry. They were not going to die, she assured Jennie. “Grandpa died because he was old. I’m not old. Your father isn’t old.” Jennie was not in the least comforted by this story. She watched the news on television, after all. “Other people die,” she said. “Even children die!”

The problems very young children have with asynchronous development is that their minds outdistance their emotional maturity, so the simple cushioning stories that adults often give young children to soften the impact of painful truths don’t work well with them. Not only do such stories not provide the cushioning the children need, the stories’ simple platitudes, so obviously untrue, are likely to be taken as adult dishonesty. Jennie had not long been identified as profoundly gifted, and her mother didn’t yet realize that she needed to deal with such issues as the inevitability of death on a much more adult level with Jennie than she had expected.

The deep and deeper human issues need to be addressed with super bright kids both more honestly and earlier than we might be prepared for. Examples of these issues—our inhumanity to each other and other life forms, our predilection for violence and warfare, our failure to protect the planet that is our only home—the list is long and more and more “in our faces” these days. Which means, of course, that we have to face these issues ourselves on a deep enough level to address them honestly from our own perspective when we talk to these children (or even when they’re within earshot). As Stephen Sondheim reminds us in a song from “Into the Woods,” Children will listen!

Many of us got our first stories about such issues from the religions of our parents or grandparents or our ethnic culture. Or from other kids, or science text books or the “mass media.” Often, as we grow up, whatever we were told from whatever source, begins to feel wrong or untrue. For myself, I long ago rejected the version of reality that was provided by my religious education—some of what was labeled wrong no longer seemed wrong to me, and what was right sometimes had begun to seem distinctly the opposite. Even worse than the loss of religious certainties in some ways, was the realization that what I had learned in school as undisputed fact (history, for instance, or even science) had too often been either purposely distorted to support a kind of cultural propaganda, or just an error that had continued to be taught even after it had been superseded or at least challenged by new information and new theories.

For myself, various “truths” began to disintegrate when my own personal experiences contradicted them. As a fiction writer, I had always intended to write “realistic fiction,” until the line between imagination and reality or between what could be and what really was could no longer be firmly drawn. There were things I experienced that I didn’t talk about in public because, except when I was talking to children, my audiences didn’t seem to me ready to hear what I would have said.

But when I was speaking to an adult audience dealing with kids at the far right tail of the curve, where unusual experiences become more common, I began to stretch the boundaries a bit. Back in the days of the Hollingworth Conference for the Highly Gifted, I explained in a keynote, for instance, that becoming a Reiki practitioner—I wasn’t yet a Reiki Master, able to teach the method to others—had ended my problem with seasonal allergies. (Reiki is an energy healing modality that originated in Japan.) All these years later, I still don’t have those allergies! One year someone wrote on a conference evaluation form that I was “too far out.” (The next year I titled my keynote “On Being Too Far Out.”)

I had, of course, found those “far out” things well-supported in books written by leading edge scientists, some of whom I knew personally, though the ideas hadn’t yet shown up in school text books. What had once been labeled “New Age” and outside the realm of rationality, began to fill the shelves at book stores even before the internet had made them readily accessible to anyone with an interest. I still find it odd that after nearly 100 years of challenging the certainties of material science and Newtonian physics, quantum physics is apparently still not a standard offering in most high schools.

Between 1992 and today, my thinking about “deep and deeper” has moved from the need to be willing to honestly talk to super gifted kids about the difficult emotional issues of human life, to being willing to honestly address questions of consciousness, reality, values and spirituality (which may or may not include religion) with them. The most important word in that sentence is “honestly.” About these issues there are seldom certainties for us other than personal experience. Being honest with them, of course, means admitting that there is “mystery” involved—as with the orbs (mysterious and sometimes colored “balls of light” often with internal mandala patterns)  that show up all over the place in photographs taken both indoors and outside at Camp Yunasa—so in talking to campers about them I make no effort to explain the phenomenon. This tends to drive the campers a little crazy. All I can say is that none of the “standard explanations” involving dust particles, moisture, or the closeness of lens to flash in digital cameras, explain them either. During my “orb slide show” last year kids got out their cameras and began taking photos and sure enough, a few orbs showed up at first, and the more photos they took the more orbs appeared. Photo above taken as two of Yunasa’s Fellows walk back to our bunks after Spirit Journey–August, 2017.

that show up all over the place in photographs taken both indoors and outside at Camp Yunasa—so in talking to campers about them I make no effort to explain the phenomenon. This tends to drive the campers a little crazy. All I can say is that none of the “standard explanations” involving dust particles, moisture, or the closeness of lens to flash in digital cameras, explain them either. During my “orb slide show” last year kids got out their cameras and began taking photos and sure enough, a few orbs showed up at first, and the more photos they took the more orbs appeared. Photo above taken as two of Yunasa’s Fellows walk back to our bunks after Spirit Journey–August, 2017.

I don’t usually write—or talk—to persuade people any more (though I used to, for sure). I write to share my thoughts, and usually some of the reasons I think them—especially when they aren’t mainstream, or not mainstream in the gifted realm. Ernest Holmes, author of Science of Mind, said, “The child-like mind is more receptive to Truth than the over intellectual.” He suggests this, I think, because children tend to be more open to mystery than those of us proud of our very good intellects. We tend to have minds stuffed with facts we’ve learned and beliefs that we think of as true, but Ernest is after something larger (and deeper), something (Truth) that he dares to capitalize without defining. And since one of his principles was always to “stay open at the top,” I’m pretty sure he would have said that Truth for us changes as we and our perceptions change. And change we humans do, if we allow it.

When I started The Deep End Facebook page back when I was new to social media, I hoped the page would encourage discussions of some of the nonrational capacities and experiences of the highly gifted that are quite common among this population (which those of us with long experience know, even though many parents are hesitant to talk about them, for fear of disbelief or ridicule). As soon as such discussions began on that page, however, some folks who limit their ideas about consciousness to the purely rational, and apparently about science to the purely material, launched attacks that closed those beginning discussions down. It can be psychologically dangerous to talk about nonrational experiences among hyper-rational gifted folk all too poised to attack. So okay, this is a blog instead, and I write it. I get to choose what I write about.

After I posted “Who Are We?” I heard from some folks that they appreciated my honesty. Maybe it’s because I’ve been in this “gifted biz” for a long time, or more likely it’s because I believe what Anita Moorjani (author of Dying to Be Me, a book about her amazing Near Death Experience) says about the need to be one’s essential self. It is that need that led me to share with Yunasa campers last year (my final year with the camp) the “evidence” I have that there is life after death. There, too, I didn’t ask them to share my interpretation of that evidence. They have to make up their own minds, as do we all. But unless we share what is deep and deeper in our own lives and experience, how will openings to new perceptions and awareness come about?

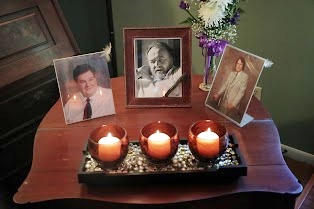

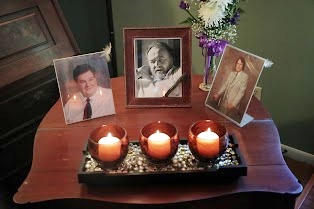

For me, it is easier to talk about death these days now that I am totally convinced by my own experiences and some astonishing evidence that it is illusion—transformation not ending. But I don’t try to convince people. I believe that honesty and authenticity have real and lasting value, no matter how others respond. (Also, I’m old enough not to care so much what people think of me as I used to.) But I must also add here that while taking the fear of death out of the picture is astonishingly liberating, it does not save us from the grief of such loss. Believe me, I know.

Tolan Memorial 2013

Tags: Aspects of Mind, asysnchronous development, Columbus Group, fear, Giftedness, Individualitiy, uniformity

fically), I know that it’s possible to create with words entire worlds and characters that a reader can “feel” as she reads to be somehow real, though made entirely of thought that can be shared by many other minds. So I have an overwhelming respect for human consciousness that includes both thought and imagination. And in a way, the fact that a person’s belief system can be so strong that it can dismiss any amount of external or written evidence that contradicts it, gives us a clue to the power of mind not just to gain new information, but also to reject it utterly. We writers have to pay attention to the need for our readers to sometimes “suspend disbelief” in order to stay with our story. And that can be tricky sometimes. “Seeing is believing” is a common saying. “Believing is seeing” is probably more accurate.

fically), I know that it’s possible to create with words entire worlds and characters that a reader can “feel” as she reads to be somehow real, though made entirely of thought that can be shared by many other minds. So I have an overwhelming respect for human consciousness that includes both thought and imagination. And in a way, the fact that a person’s belief system can be so strong that it can dismiss any amount of external or written evidence that contradicts it, gives us a clue to the power of mind not just to gain new information, but also to reject it utterly. We writers have to pay attention to the need for our readers to sometimes “suspend disbelief” in order to stay with our story. And that can be tricky sometimes. “Seeing is believing” is a common saying. “Believing is seeing” is probably more accurate.